Key Concepts, Contexts & Terms

Academic Supervisor

REGULATIONS FOR THE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR DEGREE (PHD) AT THE NORWEGIAN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (NTNU)

"Section 7.1 Appointment of academic supervisors

The Faculty appoints academic supervisors. As a general rule, the PhD candidate is to have at least two academic supervisors, of which one will be designated as the main supervisor. The main supervisor must be appointed at the time the candidate is admitted.

The main supervisor has the primary academic responsibility for the candidate. If the Faculty appoints an external main supervisor, a co-supervisor who is an academic staff member at NTNU is to be appointed.

Co-supervisors are experts in the field who provide academic supervision and who share the academic responsibility for the candidate with the main supervisor.

The provisions on impartiality in the Public Administration Act Chapter II concerning disqualification (Sections 6 to 10) [provided below] apply to the academic supervisors and appointed mentors.

All academic supervisors must hold a doctoral degree or equivalent qualification in the relevant research field and must be working actively as researchers. At least one of the appointed supervisors must have previous experience or training in academic supervision of PhD candidates.

In addition, the Faculty may appoint one or more mentors who do not meet the qualification requirements for supervisors, but who still provide supervisory assistance.

The PhD candidate and academic supervisor may ask the Faculty to appoint another supervisor for the candidate. The supervisor may not withdraw before a new supervisor has been appointed. Any disputes regarding the academic rights and obligations of the supervisor and of the candidate are to be referred by these parties to the Faculty for review and a final decision.

Section 7.2 Content of the academic supervision

The supervisors are to give advice on formulating and delimiting the thematic area and research questions, discuss and assess hypotheses and methods, discuss the results and the interpretation of these, discuss the structure and work on the thesis, including the outline, choice of language, documentation, etc., and provide guidance on the academic literature and data available in libraries, archives, etc. The supervisors must also advise the candidate on issues related to research ethics in connection with the thesis.

The candidate must have regular contact with his or her supervisors. The frequency of contact between the parties is to be stated in the annual reporting of progress; cf. Section 9.

The candidate and supervisors have a mutual obligation to keep each other informed about the PhD Regulations for NTNU Approved by the Board of NTNU on 23 January 2012 7 progress of the work and to assess it in relation to the project description.

The supervisors are required to follow up academic issues that may cause a delay in the progression of the candidate’s PhD education, so that it can be completed within the nominal period of study."

(Source: PhD Regulations for NTNU Approved by the Board of NTNU on 23 January 2012: REGULATIONS FOR THE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR DEGREE (PHD) AT THE NORWEGIAN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (NTNU) Norwegian: Forskrift for graden philosophiae doctor (ph.d.) ved Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelig universitet (NTNU))

Act relating to procedure in cases concerning the public administration (Public Administration Act)

"Chapter II. Concerning disqualification

Section 6. (requirements as to impartiality)

§ 6. (habilitetskrav).

A public official shall be disqualified from preparing the basis for a decision or from making any decision in an administrative case

If the superior official is disqualified, the case may not be decided by any directly subordinate official in the same administrative agency.

The rules governing disqualification shall not apply if it is evident that the official's connection with the case or the parties will not influence his standpoint and neither public nor private interests indicate that he should stand down.

The scope of the second and fourth paragraphs may be further specified in regulations prescribed by the King."

Section 7. (Provisional decision) Regardless of whether an official is disqualified, he may deal with a case or make a provisional decision in a case if it cannot be postponed without causing considerable inconvenience or harm.

Section 8. (Decision concerning the question of disqualification)

The official shall himself decide whether he is disqualified. He shall submit the question to his immediate superior for decision if a party so requests and this may be done without undue loss of time, or if the official himself otherwise finds reason to do so.

In collegiate bodies the decision shall be made by the body itself, without the participation of the member concerned. If, in one and the same case, the question of disqualification should arise in respect of several members, none of them may participate in the decision regarding their own or another member's disqualification, unless the collegiate body would otherwise lack a quorum for deciding the question. In the latter case all attending members shall participate.

A member shall give ample notice of any circumstance which disqualifies or may disqualify him. Before the question is decided, his deputy or other substitute should be summoned to attend and participate in the decision if this may be done without undue expense or loss of time.

Section 9. (Appointment of a substitute)

If an official is disqualified, a substitute shall, if necessary, be appointed or elected in his stead.

If the appointment of a substitute will be particularly inconvenient, the King may decide that the case in question shall be transferred to a coordinate or superior administrative agency

Section 10. (Persons to whom the rules on disqualification shall apply) Besides public officials, the provisions of this Chapter shall apply correspondingly to any other person who performs services or work for an administrative agency. The provisions shall not apply to members of the Council of State in their capacity as members of the government."

(Source: Lovdata.no: English: Act relating to procedure in cases concerning the public administration (Public Administration Act) Norwegian: Lov om behandlingsmåten i forvaltningssaker (forvaltningsloven) (Forvaltningsloven – fvl)

Authorship

Who Is an Author?

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)

"The ICMJE recommends that authorship be based on the following 4 criteria:

Authorship (continued)

"Scientific integrity, truthfulness and accountability"

Authorship (continued)

"Misusing authorship to build career" ("Misbruker forfatterskap for å bygge karriere")

Authorship (continued)

"Freeloading in biomedical research"

"Thousands of scientists publish a paper every five days"

To highlight uncertain norms in authorship, John P. A. Ioannidis, Richard Klavans and Kevin W. Boyack identified the most prolific scientists of recent years.

Birth

Citation Distortions

"How citation distortions create unfounded authority: analysis of a citation network"

"Vocabulary of citation distortions

Citation

Citation Manipulation

"Citation manipulation refers to the following types of behaviour:

Citation Doping & Stacking

"Hundreds of extreme self-citing scientists revealed in new database"

"Some highly cited academics seem to be heavy self-promoters — but researchers warn against policing self-citation."

"Italy’s rise in research impact pinned on ‘citation doping'"

"Citation of Italian-authored papers by Italian researchers rose after the introduction of metrics-based thresholds for promotions."

"Brazilian citation scheme outed"

"Thomson Reuters suspends journals from its rankings for ‘citation stacking’."

Cognitive dissonance "In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort (psychological stress) experienced by a person who simultaneously holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. The occurrence of cognitive dissonance is a consequence of a person's performing an action that contradicts personal beliefs, ideals, and values; and also occurs when confronted with new information that contradicts said beliefs, ideals, and values." (Source: Wikipedia: Cognitive dissonance)

Confirmation bias "the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one's existing beliefs or theories." (Source: Wikipedia: Confirmation bias)

Conflate-to-obfuscate a technique whereby two or more sets of information, texts, ideas, methods, etc. are combined into one set and presented to be synonymous in an effort to confuse the real differences between or among them. This is also known as combine-to-confuse and fuse-to-confuse. (See: "Confused on conflated" Merrill Perlman. Columbia Journalism Review February 9, 2015)

“The rise of Italy in impact rankings appears to be the fruit of a collective ‘citation doping’ induced by the new policies,” says Alberto Baccini, an economist at the University of Siena in Italy who led the study, published on 11 September in PLoS ONE1.

REGULATIONS FOR THE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR DEGREE (PHD) AT THE NORWEGIAN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (NTNU)

"Section 7.1 Appointment of academic supervisors

The Faculty appoints academic supervisors. As a general rule, the PhD candidate is to have at least two academic supervisors, of which one will be designated as the main supervisor. The main supervisor must be appointed at the time the candidate is admitted.

The main supervisor has the primary academic responsibility for the candidate. If the Faculty appoints an external main supervisor, a co-supervisor who is an academic staff member at NTNU is to be appointed.

Co-supervisors are experts in the field who provide academic supervision and who share the academic responsibility for the candidate with the main supervisor.

The provisions on impartiality in the Public Administration Act Chapter II concerning disqualification (Sections 6 to 10) [provided below] apply to the academic supervisors and appointed mentors.

All academic supervisors must hold a doctoral degree or equivalent qualification in the relevant research field and must be working actively as researchers. At least one of the appointed supervisors must have previous experience or training in academic supervision of PhD candidates.

In addition, the Faculty may appoint one or more mentors who do not meet the qualification requirements for supervisors, but who still provide supervisory assistance.

The PhD candidate and academic supervisor may ask the Faculty to appoint another supervisor for the candidate. The supervisor may not withdraw before a new supervisor has been appointed. Any disputes regarding the academic rights and obligations of the supervisor and of the candidate are to be referred by these parties to the Faculty for review and a final decision.

Section 7.2 Content of the academic supervision

The supervisors are to give advice on formulating and delimiting the thematic area and research questions, discuss and assess hypotheses and methods, discuss the results and the interpretation of these, discuss the structure and work on the thesis, including the outline, choice of language, documentation, etc., and provide guidance on the academic literature and data available in libraries, archives, etc. The supervisors must also advise the candidate on issues related to research ethics in connection with the thesis.

The candidate must have regular contact with his or her supervisors. The frequency of contact between the parties is to be stated in the annual reporting of progress; cf. Section 9.

The candidate and supervisors have a mutual obligation to keep each other informed about the PhD Regulations for NTNU Approved by the Board of NTNU on 23 January 2012 7 progress of the work and to assess it in relation to the project description.

The supervisors are required to follow up academic issues that may cause a delay in the progression of the candidate’s PhD education, so that it can be completed within the nominal period of study."

(Source: PhD Regulations for NTNU Approved by the Board of NTNU on 23 January 2012: REGULATIONS FOR THE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR DEGREE (PHD) AT THE NORWEGIAN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (NTNU) Norwegian: Forskrift for graden philosophiae doctor (ph.d.) ved Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelig universitet (NTNU))

Act relating to procedure in cases concerning the public administration (Public Administration Act)

"Chapter II. Concerning disqualification

Section 6. (requirements as to impartiality)

§ 6. (habilitetskrav).

A public official shall be disqualified from preparing the basis for a decision or from making any decision in an administrative case

- a) if he himself is a party to the case;

- b) if he is related by blood or by marriage to a party in direct line of ascent or descent, or collaterally as close as a sibling;

- c) if he is or has been married or is engaged to a party, or is the foster parent or foster child of a party;

- d) if he is the guardian or agent of a party to the case or has been the guardian or agent of a party after the case began;

- e) if he is the head of, or holds a senior position in, or is a member of the board of directors or the corporate assembly of

- 1.a cooperative company, or an association, savings bank or foundation that is a party to the case, or

- 2.a company which is a party to the case. Nevertheless, this does not apply to a person who performs services or work for a company that is wholly-owned by the State and/or a municipality, and such company, either alone or together with other similar companies or the State and/or a municipality, wholly owns the company that is a party to the case.

If the superior official is disqualified, the case may not be decided by any directly subordinate official in the same administrative agency.

The rules governing disqualification shall not apply if it is evident that the official's connection with the case or the parties will not influence his standpoint and neither public nor private interests indicate that he should stand down.

The scope of the second and fourth paragraphs may be further specified in regulations prescribed by the King."

Section 7. (Provisional decision) Regardless of whether an official is disqualified, he may deal with a case or make a provisional decision in a case if it cannot be postponed without causing considerable inconvenience or harm.

Section 8. (Decision concerning the question of disqualification)

The official shall himself decide whether he is disqualified. He shall submit the question to his immediate superior for decision if a party so requests and this may be done without undue loss of time, or if the official himself otherwise finds reason to do so.

In collegiate bodies the decision shall be made by the body itself, without the participation of the member concerned. If, in one and the same case, the question of disqualification should arise in respect of several members, none of them may participate in the decision regarding their own or another member's disqualification, unless the collegiate body would otherwise lack a quorum for deciding the question. In the latter case all attending members shall participate.

A member shall give ample notice of any circumstance which disqualifies or may disqualify him. Before the question is decided, his deputy or other substitute should be summoned to attend and participate in the decision if this may be done without undue expense or loss of time.

Section 9. (Appointment of a substitute)

If an official is disqualified, a substitute shall, if necessary, be appointed or elected in his stead.

If the appointment of a substitute will be particularly inconvenient, the King may decide that the case in question shall be transferred to a coordinate or superior administrative agency

Section 10. (Persons to whom the rules on disqualification shall apply) Besides public officials, the provisions of this Chapter shall apply correspondingly to any other person who performs services or work for an administrative agency. The provisions shall not apply to members of the Council of State in their capacity as members of the government."

(Source: Lovdata.no: English: Act relating to procedure in cases concerning the public administration (Public Administration Act) Norwegian: Lov om behandlingsmåten i forvaltningssaker (forvaltningsloven) (Forvaltningsloven – fvl)

Authorship

Who Is an Author?

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)

"The ICMJE recommends that authorship be based on the following 4 criteria:

- Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved." (Source: International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, "Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals Updated December 2016" http://www.icmje.org/ & http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf, resectively)

Authorship (continued)

"Scientific integrity, truthfulness and accountability"

- "5 Researchers must respect the contributions of other researchers and observe standards of authorship and cooperation.

Researchers must observe good publication practice. They must clarify individual responsibilities in group work as well as the rules for co-authorship. Honorary authorship is unacceptable. When several authors contribute, each authorship must be justified. Justified authorship is defined by four criteria, in accordance with the criteria drawn up by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) 3:

a) Researchers must have made a substantial contribution to the conception and design or the data acquisition or the data analysis and interpretation; and

b) researchers must have contributed to drafting the manuscript or critical revision of the intellectual content of the publication; and

c) researchers must have approved the final version before publication; and

d) researchers must be able to accept responsibility for and be accountable for the work as a whole (albeit not necessarily all technical details) unless otherwise specified.

All authors in a multidisciplinary publication must be able to account for the part or parts for which they have been responsible in the research work, and which part or parts are the responsibility of other contributors.

All those who meet criterion a) must be able to meet b) and c). Contributors who do not fulfil all the criteria must be acknowledged." (Source: "Scientific integrity, truthfulness and accountability" from "Guidelines for research ethics in science and technology" Issued by The Norwegian National Committee for Research Ethics in Science and Technology (2016). Text: The Norwegian National Committees for Research Ethics, Last updated: Tuesday, June 28, 2016)

Authorship (continued)

"Misusing authorship to build career" ("Misbruker forfatterskap for å bygge karriere")

- Authorship is easy to count, but difficult to handle. Every third researcher admits having awarded co-authorship to one who does not deserve it.

Forfatterskap er lett å telle, men vanskelig å håndtere. Hver tredje forsker innrømmer å ha tildelt medforfatterskap til en som ikke fortjener det. (Source: "Misusing authorship to build career" ("Misbruker forfatterskap for å bygge karriere") Ida Irene Bergstrøm. De nasjonale forskningsetiske komiteene. Sist oppdatert: 21. mars 2018. Original version: "Honor Where Honor is Due" ("Æres den som æres bør") Ida Irene Bergstrøm, Editor/Redaktor Forsknings etikk Et magasin fra De nasjonale forskningsetiske komiteene. NR. 1 • Mars 2018 • 18. årgang. p. 4-7.) - When the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) made their first guidelines for articles in biomedical journals in 1979, no authorship was mentioned, says Charlotte Haug.

Haug is an international correspondent for The New England Journal of Medicine, and senior researcher at SINTEF. From 2002-2015 she was editor of the magazine for the Norwegian Medical Association.

Da den internasjonale komiteen for medisinske tidsskriftredaktører (ICMJE) lagde sine første retningslinjer for artikler i biomedisinske tidsskrifter i 1979, var ikke forfatterskap nevnt, forteller Charlotte Haug.

Haug er internasjonal korrespondent for The New England Journal of Medicine, og seniorforsker ved SINTEF. Fra 2002-2015 var hun redaktør for Tidsskrift for den norske legeforening.

"In 1979, it was thought that everyone had the same meaning about what the authorship meant," said Haug.

Only in 1988 came the first criteria for authorship in the ICMJE Guidelines, also known as the Vancouver Recommendations."

– I 1979 tenkte man at alle hadde samme mening om hva forfatterskap innebar, sier Haug.

Først i 1988 kom de første kriteriene om forfatterskap i ICMJE-retningslinjene, også kjent som Vancouveranbefalingene.

"The following updates have been about refining these first criteria," says Haug.

– Påfølgende oppdateringer har handlet om å finpusse disse første kriteriene, forteller Haug.

"Until 2000, it was argued whether those who had gathered data and contributed in analyzes should be included. Over the 2000s, a number of profiled cases came about falsification and manufacturing.

In 2013, therefore, we received a fourth criterion that states that everyone is responsible for the entire article. That means everyone is responsible for saying that "I believe in this - and I think something is wrong, I am responsible for investigating it."

– Frem til 2000 kranglet man om hvorvidt de som hadde samlet inn data og bidratt i analyser skulle få være med. Utover 2000-tallet kom en rekke profilerte saker om falsifisering og fabrikkering.

I 2013 fikk vi derfor et fjerde kriterium som sier at alle er ansvarlige for hele artikkelen. Det betyr at alle er ansvarlige for å si at «jeg tror på dette – og tror jeg noe er feil, har jeg ansvar for å få det undersøkt».

Other discussions have been about wrongful authors who have not contributed and thus should not have their name there. This is often called honorary authorship or guest authorship. Another problem is ghost writers - writers who have contributed or might be behind the entire article, but do not stand as authors.

Andre diskusjoner har handlet om urettmessige forfattere som ikke har bidratt og dermed ikke burde hatt sitt navn der. Dette kalles gjerne æresforfatterskap, eller gjesteforfatterskap. Et annet problem er ghost writers – forfattere som har bidratt eller kanskje står bak hele artikkelen, men ikke står som forfattere.

"Several cases revealed that agencies had been paid by the pharmaceutical industry to write articles," says Haug.

– Flere saker avslørte at byråer hadde blitt betalt av legemiddelindustrien for å skrive artikler, forteller Haug. (Source: ibid.) - Charlotte Haug recalls that the ICMJE criteria have been developed by editors, to know who they can hold responsible for the text they publish.

Charlotte Haug minner om at ICMJE-kriteriene er utviklet av redaktører, for å vite hvem de kan holde ansvarlig for teksten de publiserer.- "There is a reason why this type of criteria was first developed in medicine and health. It is essential that research teams have done what has been done. Anything else can actually put patients at risk. The ICMJE guidelines are not just four criteria," emphasizes the former journal editor. "There are lots of text that elaborate on what they are about and how they should be interpreted."

– Det er en grunn til at denne typen kriterier først ble utviklet i medisin og helse. Det er helt vesentlig at det er hold i forskningen, at man har gjort det som står der. Noe annet kan faktisk sette pasienter i fare.

ICMJE-retningslinjene er dessuten ikke bare fire kriterier, understreker den tidligere tidsskriftredaktøren. Det er masse tekst som utdyper hva de handler om og hvordan de skal tolkes.

"There is an incredible amount of conflict tied to authorship, it is simply an incredibly large conflict area. It's hardly possible to believe if you have not been in the research world, "says Haug.

– Det er utrolig mye konflikt knytta til forfatterskap, det er rett og slett et utrolig stort konfliktområde. Det er nesten ikke til å tro hvis du ikke har vært inne i forskningsverdenen, sier Haug.

"At the same time, multi-literacy in medicine is a form of quality assurance. You should not sit in a room alone and keep up with yours. It's not that you necessarily cheat consciously, but you can leave results that do not fit completely, slip away, or move some numbers. It is easy and human to believe very much in one's own hypothesis. Therefore, you must be more. If Sudbø had been the sole author, as it practically looked like he was, the editors would have suspected at once."

– Samtidig er det sånn at flerforfatterskap innen medisinen er en form for kvalitetssikring. Du skal ikke sitte i et rom alene og holde på med ditt. Det er ikke det at man da nødvendigvis jukser bevisst, men man kan la resultater som ikke passer helt, gli bort, eller flytte noen tall. Det er lett og menneskelig å tro veldig på sin egen hypotese. Derfor skal man være flere. Hvis Sudbø hadde vært eneforfatter, som det i praksis nesten så ut som han var, så ville redaktørene fattet mistanke med en gang. (Source: ibid.)

- "There is a reason why this type of criteria was first developed in medicine and health. It is essential that research teams have done what has been done. Anything else can actually put patients at risk. The ICMJE guidelines are not just four criteria," emphasizes the former journal editor. "There are lots of text that elaborate on what they are about and how they should be interpreted."

- However, Charlotte Haug is tired of discussing authorship criteria.

Charlotte Haug er imidlertid lei av å diskutere forfatterskapskriterier.- "This should be expressed in discussions about what is happening at the institutions. What kind of culture it is for collaboration, for sharing data. It's a bit like #metoo. We can hold on for a while and take the bad ones. But first and foremost, this is about culture that is established over a long period of time, which makes it clear what is going beyond borders. It should trigger discussions about how we actually organize and conduct research. What we mean by researching and writing together."

– Det dette bør munne ut i er diskusjoner om hva som foregår på institusjonene. Hva slags kultur det er for samarbeid, for deling av data. Det er litt som med #metoo. Vi kan godt holde på en stund til og ta de slemme. Men først og fremst dreier dette seg om kultur som etableres over lang tid, der det blir klart hva som er å overskride grenser. Det bør utløse diskusjoner om hvordan vi egentlig organiserer og driver med forskning. Hva vi mener med å forske, og å skrive sammen. (Source: ibid.)

- "This should be expressed in discussions about what is happening at the institutions. What kind of culture it is for collaboration, for sharing data. It's a bit like #metoo. We can hold on for a while and take the bad ones. But first and foremost, this is about culture that is established over a long period of time, which makes it clear what is going beyond borders. It should trigger discussions about how we actually organize and conduct research. What we mean by researching and writing together."

Authorship (continued)

"Freeloading in biomedical research"

- Abstract

The surge in the number of authors per article in the biomedical field makes it difficult to quantify the contribution of individual authors. Conventional citation metrics are typically based on the number of publications and the number of citations generated by a scientist, thereby disregarding the contribution of co-authors. Previously we developed the p-index that estimates the dependency of a scientist on co-authors during their career. In this study we aimed to evaluate the ability of the p-index to identify researchers with a relatively high degree of scientific dependence on co-authors. For this purpose, we retrieved articles, which were rejected for publication in Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis and subsequently published elsewhere. Assuming that authors who were added to a later version of these articles would not fulfill the full authorship criteria, we tested whether these authors showed a larger dependency on co-authors during their scientific career as would be evident from a higher p-index. In accordance with this hypothesis, authors who were added on later versions of articles showed a higher p-index than their peers, indicating an enduring pattern of dependency on other co-authors for publishing their work. This study underscores that questionable authorship practices are endemic to the biomedical research, which calls for alternative methods to evaluate a scientist’s qualities. (Source: "Freeloading in biomedical research" Rozing, M.P., van Leeuwen, T.N., Reitsma, P.H. et al. Scientometrics (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2984-3)

"Thousands of scientists publish a paper every five days"

To highlight uncertain norms in authorship, John P. A. Ioannidis, Richard Klavans and Kevin W. Boyack identified the most prolific scientists of recent years.

- "Widely used citation and impact metrics should be adjusted accordingly. For instance, if adding more authors diminished the credit each author received, unwarranted multi-authorship might go down. We found that the 30 hyperprolific authors who seemed to benefit the most from co-authorship numbered 6 cardiologists and 24 epidemiologists (including those working on population genetics studies). (For these scientists, the ratio of their Hirsch H index to their co-authorship-adjusted Schreiber Hm index was higher; see Supplementary Information.)

Overall, hyperprolific authors might include some of the most energetic and excellent scientists. However, such modes of publishing might also reflect idiosyncratic field norms, to say the least. Loose definitions of authorship, and an unfortunate tendency to reduce assessments to counting papers, muddy how credit is assigned. One still needs to see the total publishing output of each scientist, benchmarked against norms for their field. And of course, there is no substitute for reading the papers and trying to understand what the authors have done." (Source: "Thousands of scientists publish a paper every five days" To highlight uncertain norms in authorship, John P. A. Ioannidis, Richard Klavans and Kevin W. Boyack identified the most prolific scientists of recent years. Nature 561, 167-169 (2018) 12 SEPTEMBER 2018. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-06185-8)

Birth

- Post-term birth birth >=42 completed gestational weeks

- Preterm birth birth at a gestational age <37 completed gestational weeks

- Term birth birth >=37 and <42 completed gestational weeks

Citation Distortions

"How citation distortions create unfounded authority: analysis of a citation network"

"Vocabulary of citation distortions

Citation

- Both scholarly and social forms: the scholarly form connects statements to the broader medical literature, the social form (social citation) includes self serving and persuasive subtypes

- Self serving citation is always a distortion

- Persuasive citation may be necessary to communicate new, sound claims to the scientific community; it may, however, have distorted uses—citation bias, amplification, and invention

- Systematic ignoring of papers that contain content conflicting with a claim

- Bolster claim; justifying animal models to provide opportunities to amplify claim

- Expansion of a belief system without data

- Citation made to papers that don’t contain primary data, increasing the number of citations supporting the claim without presenting data addressing it

- Citation diversion—citing content but claiming it has a different meaning, thereby diverting its implication

- Citation transmutation—the conversion of hypothesis into fact through the act of citation alone

- Back door invention—repeated misrepresentation of abstracts as peer reviewed papers to fool readers into believing that claims are based on peer reviewed published methods and data

- Dead end citation—support of a claim with citation to papers that do not contain content addressing the claim

- Title invention—reporting of “experimental results” in a paper’s title, even though the paper does not report the performance or results of any such experiments"

(Source: "How citation distortions create unfounded authority: analysis of a citation network" Steven A Greenberg. BMJ 2009;339:b2680)

Citation Manipulation

"Citation manipulation refers to the following types of behaviour:

- Excessive citation of an author’s research by the author (ie, self-citation by authors) as a means solely of increasing the number of citations of the author’s work;

- Excessive citation of articles from the journal in which the author is publishing a research article as a means solely of increasing the number of citations of the journal; or

- Excessive citation of the work of another author or journal, sometimes referred to as ‘honorary’ citations (eg, the editor-in-chief of the journal to which one is submitting a manuscript or a well-known scholar in the field of the researcher) or ‘citation stacking’ solely to contribute to the citations of the author(s)/ journal(s) in question.

Citation Doping & Stacking

"Hundreds of extreme self-citing scientists revealed in new database"

"Some highly cited academics seem to be heavy self-promoters — but researchers warn against policing self-citation."

- "Vaidyanathan, a computer scientist at the Vel Tech R&D Institute of Technology, a privately run institute, is an extreme example: he has received 94% of his citations from himself or his co-authors up to 2017, according to a study in PLoS Biology this month1. He is not alone. The data set, which lists around 100,000 researchers, shows that at least 250 scientists have amassed more than 50% of their citations from themselves or their co-authors, while the median self-citation rate is 12.7%."

The study could help to flag potential extreme self-promoters, and possibly ‘citation farms’, in which clusters of scientists massively cite each other, say the researchers. “I think that self-citation farms are far more common than we believe,” says John Ioannidis, a physician at Stanford University in California who specializes in meta-science — the study of how science is done — and who led the work. “Those with greater than 25% self-citation are not necessarily engaging in unethical behaviour, but closer scrutiny may be needed,” he says." (Source: "Hundreds of extreme self-citing scientists revealed in new database" Richard Van Noorden & Dalmeet Singh Chawla, Nature 572, 578-579 (2019) doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02479-7)

"Italy’s rise in research impact pinned on ‘citation doping'"

"Citation of Italian-authored papers by Italian researchers rose after the introduction of metrics-based thresholds for promotions."

- "Italy is climbing international rankings of research impact, but that doesn’t mean the country’s science has improved or become more influential. An analysis suggests the upward trend could be largely the result of Italian academics referencing each other’s articles more heavily to satisfy controversial management targets at universities.

The rise of Italy in impact rankings appears to be the fruit of a collective ‘citation doping’ induced by the new policies,” says Alberto Baccini, an economist at the University of Siena in Italy who led the study, published on 11 September in PLoS ONE." (Source: "Italy’s rise in research impact pinned on ‘citation doping’" Richard Van Noorden, Nature, 13 SEPTEMBER 2019, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221212 (2019))

"Brazilian citation scheme outed"

"Thomson Reuters suspends journals from its rankings for ‘citation stacking’."

- "Mauricio Rocha-e-Silva thought that he had spotted an easy way to raise the profiles of Brazilian journals. From 2009, he and several other editors published articles containing hundreds of references to papers in each others’ journals — in order, he says, to elevate the journals’ impact factors.

Because each article avoided citing papers published by its own journal, the agreement flew under the radar of analyses that spot extremes in self-citation — until 19 June, when the pattern was discovered. Thomson Reuters, the firm that calculates and publishes the impact factor, revealed that it had designed a program to spot concentrated bursts of citations from one journal to another, a practice that it has dubbed ‘citation stacking’. Four Brazilian journals were among 14 to have their impact factors suspended for a year for such stacking. And in July, Rocha-e-Silva was fired from his position as editor of one of them, the journal Clinics, based in São Paulo." - "The journals flagged by the new algorithm extend beyond Brazil — but only in that case has an explanation for the results emerged. Rocha-e-Silva says the agreement grew out of frustration with his country’s fixation on impact factor. In Brazil, an agency in the education ministry, called CAPES, evaluates graduate programmes in part by the impact factors of the journals in which students publish research. As emerging Brazilian journals are in the lowest ranks, few graduates want to publish in them. This vicious cycle, in his view, prevents local journals improving."

Cognitive dissonance "In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort (psychological stress) experienced by a person who simultaneously holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. The occurrence of cognitive dissonance is a consequence of a person's performing an action that contradicts personal beliefs, ideals, and values; and also occurs when confronted with new information that contradicts said beliefs, ideals, and values." (Source: Wikipedia: Cognitive dissonance)

Confirmation bias "the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one's existing beliefs or theories." (Source: Wikipedia: Confirmation bias)

Conflate-to-obfuscate a technique whereby two or more sets of information, texts, ideas, methods, etc. are combined into one set and presented to be synonymous in an effort to confuse the real differences between or among them. This is also known as combine-to-confuse and fuse-to-confuse. (See: "Confused on conflated" Merrill Perlman. Columbia Journalism Review February 9, 2015)

- Conflate: combine (two or more sets of information, texts, ideas, etc.) into one

- Obfuscate: make obscure, unclear, or unintelligible; bewilder (someone)

“The rise of Italy in impact rankings appears to be the fruit of a collective ‘citation doping’ induced by the new policies,” says Alberto Baccini, an economist at the University of Siena in Italy who led the study, published on 11 September in PLoS ONE1.

Corruption

"CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS OR ORGANIZATIONS OF CORRUPT INDIVIDUALS? TWO TYPES OF ORGANIZATION-LEVEL CORRUPTION"

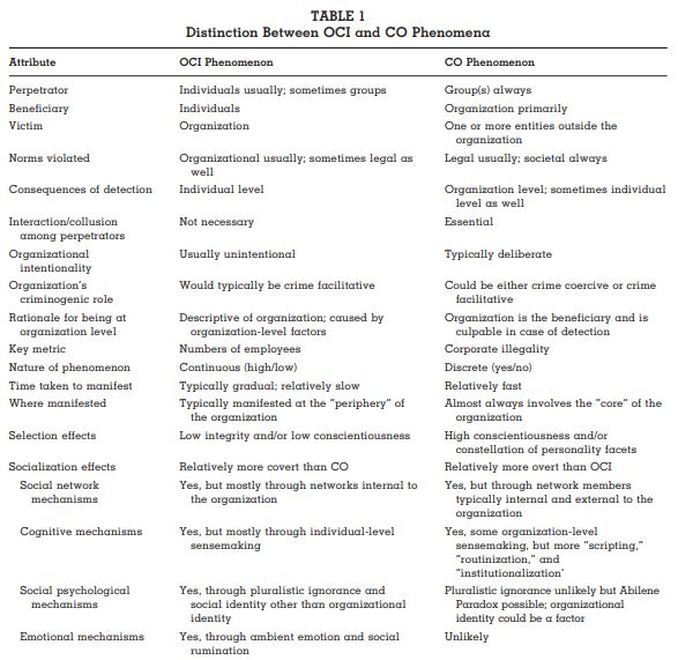

"CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS OR ORGANIZATIONS OF CORRUPT INDIVIDUALS? TWO TYPES OF ORGANIZATION-LEVEL CORRUPTION"

- "We focus on two fundamental dimensions of corruption in organizations: (1) whether the individual or the organization is the beneficiary of the corrupt activity and (2) whether the corrupt behavior is undertaken by an individual actor or by two or more actors. We use these dimensions to define a new conceptualization of corruption at the organization level: the organization of corrupt individuals. We contrast this conceptualization with the prevailing concept of organizational corruption and develop propositions that highlight their differences." (Source: "CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS OR ORGANIZATIONS OF CORRUPT INDIVIDUALS? TWO TYPES OF ORGANIZATION-LEVEL CORRUPTION" JONATHAN PINTO, CARRIE R. LEANA, FRITS K. PIL. Academy of Management Review 2008, Vol. 33, No. 3, 685–709. p. 685)

- '"We offer our typology of corruption as a way of clarifying theory and research at the organization level. We also aim to address why different types of organizations may manifest different corruption phenomena, or why attempting to control one form of corruption may unwittingly lead to the creation of the other. Our multilevel approach encompasses bottom-up and top-down corruption, both composition and compilation emergent processes, and both selection and socialization in organizations. Finally, we address the relatively small but important literature on criminogenic mechanisms—that is, mechanisms that produce or tend to produce crime or criminal behavior. While this literature focuses almost exclusively on “crime-coercive” mechanisms, we focus more on “crime-facilitative” ones (Needleman & Needleman, 1979). (Source: Ibid., p. 685-686)

- "TWO TYPES OF CORRUPTION AT THE ORGANIZATION LEVEL

Using the two dimensions of beneficiary and collusion, we suggest that corruption at the organization level can manifest itself through two very distinct phenomena: an organization of corrupt individuals (OCI), in which a significant proportion of an organization’s members act in a corrupt manner primarily for their personal benefit (similar to the economics perspective), and a corrupt organization (CO), in which a group collectively acts in a corrupt manner for the benefit of the organization (similar to the sociology perspective). In both forms of corruption, the organization is the focal unit—that is, the level to which generalizations are made—and both the levels of measurement and the levels of analysis can be at the individual, group, organization, and environmental levels. (Source: Ibid., p 688)

Council of Science Editors is a dynamic community of editorial professionals dedicated to the responsible and effective communication of science.

Dates All dates are in dd.mm.yyyy format unless otherwise indicated.

Death

Dolichocephaly, more commonly "long head" or "breech head"; Cephalic index (CI) <= 75

Doublethink "Doublethink is the act of simultaneously accepting two mutually contradictory beliefs as correct, often in distinct social contexts. [1] Doublethink is related to, but differs from, hypocrisy and neutrality. Also related is cognitive dissonance, in which contradictory beliefs cause conflict in one's mind. Doublethink is notable due to a lack of cognitive dissonance—thus the person is completely unaware of any conflict or contradiction." (Source: Wikipedia: Doublethink)

Estimation vs. Prediction

The terms "estimation" and "prediction" have been conflated and and are commonly used interchangeably as synonyms in the ultrasound biometry literature, which is unfortunate. Consequently, this document will also use these terms somewhat interchangeably. However, in classical statistical inference there is a clear distinction between an estimator and predictor. An estimator uses data to guess at a parameter or coefficient while a predictor (e.g., an ultrasound fetal metric measurement) uses data to guess at some random value (e.g., GA or EDD, depending on the model) that is not part of the dataset used to create the model (i.e., regression line/curve, etc.). Estimation accounts for uncertainty in the regression line/curve (i.e., the model). Prediction accounts for uncertainty in the regression line/curve (i.e., the model) plus the uncertainty in the individual observation (e.g., an individual ultrasound fetal metric measurement). Therefore, since both estimation and prediction account for uncertainty in the regression line or curve (i.e. the model), some slack will be cut and both terms, "estimation" and "prediction" will be used in reference to model-derived predictions/estimations (e.g., GA or EDD predictions/estimations) made from predictors (i.e., fetal metric measurements: CRL, HC, BPD, FL, AC, MAD, etc.)

Given that the terms "estimation" and "prediction" have been conflated and used extensively as synonyms there are those who would similarly conflate other terms such as "estimate" and "calculate." For example, NCFM eSnurra Group intentionally conflate the "prediction/estimation" of GA with the "prediction/estimation" of EDD in order to obfuscate the differences between these 2 completely different methods of establishing GA and EDD, respectively, for individual pregnancies. Moreover, NCFM eSnurra Group then describes these methods as being synonymous to healthcare authorities, healthcare professionals and the general public when, in reality, these 2 separate prediction/estimation methods have distinct differences and each with very different "prediction/estimation" objectives. This science-bending, conflate-to-obfuscate strategy for GA and EDD prediction/estimation is a real-world example of bending policy-relevant science; and, unfortunately, in this example Norway's national obstetric & fetal medicine policy was bent to cause increased medical risks, critical medical mistakes and grievous medical harms (including perinatal death), unnecessarily, for some of Norway's women and their fetuses/babies.

- White Paper on Publication Ethics (Download a PDF of the entire White Paper)

Dates All dates are in dd.mm.yyyy format unless otherwise indicated.

Death

- Infant death death <1 year of life

- Perinatal death stillbirth or death <=6 completed days of life

- Neonatal death death >6 and <=27 completed days of life; Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR)

- Post-neonatal death death >= 28th completed day of life and <= 1 completed year of life

Dolichocephaly, more commonly "long head" or "breech head"; Cephalic index (CI) <= 75

Doublethink "Doublethink is the act of simultaneously accepting two mutually contradictory beliefs as correct, often in distinct social contexts. [1] Doublethink is related to, but differs from, hypocrisy and neutrality. Also related is cognitive dissonance, in which contradictory beliefs cause conflict in one's mind. Doublethink is notable due to a lack of cognitive dissonance—thus the person is completely unaware of any conflict or contradiction." (Source: Wikipedia: Doublethink)

- "DOUBLETHINK means the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them. The Party intellectual knows in which direction his memories must be altered; he therefore knows that he is playing tricks with reality; but by the exercise of DOUBLETHINK he also satisfies himself that reality is not violated. The process has to be conscious, or it would not be carried out with sufficient precision, but it also has to be unconscious, or it would bring with it a feeling of falsity and hence of guilt" (Source: George Orwell, "1984" Part Two, Chapter 9)

- "It was as though some huge force were pressing down upon you — something that penetrated inside your skull, battering against your brain, frightening you out of your beliefs, persuading you, almost, to deny the evidence of your senses. In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it. It was inevitable that they should make that claim sooner or later: the logic of their position demanded it. Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality, was tacitly denied by their philosophy. The heresy of heresies was common sense." (Source: George Orwell, "1984" Part One, Chapter 7)

- "Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two makes four. If that is granted, all else follows" (Source: ibid.)

Estimation vs. Prediction

The terms "estimation" and "prediction" have been conflated and and are commonly used interchangeably as synonyms in the ultrasound biometry literature, which is unfortunate. Consequently, this document will also use these terms somewhat interchangeably. However, in classical statistical inference there is a clear distinction between an estimator and predictor. An estimator uses data to guess at a parameter or coefficient while a predictor (e.g., an ultrasound fetal metric measurement) uses data to guess at some random value (e.g., GA or EDD, depending on the model) that is not part of the dataset used to create the model (i.e., regression line/curve, etc.). Estimation accounts for uncertainty in the regression line/curve (i.e., the model). Prediction accounts for uncertainty in the regression line/curve (i.e., the model) plus the uncertainty in the individual observation (e.g., an individual ultrasound fetal metric measurement). Therefore, since both estimation and prediction account for uncertainty in the regression line or curve (i.e. the model), some slack will be cut and both terms, "estimation" and "prediction" will be used in reference to model-derived predictions/estimations (e.g., GA or EDD predictions/estimations) made from predictors (i.e., fetal metric measurements: CRL, HC, BPD, FL, AC, MAD, etc.)

Given that the terms "estimation" and "prediction" have been conflated and used extensively as synonyms there are those who would similarly conflate other terms such as "estimate" and "calculate." For example, NCFM eSnurra Group intentionally conflate the "prediction/estimation" of GA with the "prediction/estimation" of EDD in order to obfuscate the differences between these 2 completely different methods of establishing GA and EDD, respectively, for individual pregnancies. Moreover, NCFM eSnurra Group then describes these methods as being synonymous to healthcare authorities, healthcare professionals and the general public when, in reality, these 2 separate prediction/estimation methods have distinct differences and each with very different "prediction/estimation" objectives. This science-bending, conflate-to-obfuscate strategy for GA and EDD prediction/estimation is a real-world example of bending policy-relevant science; and, unfortunately, in this example Norway's national obstetric & fetal medicine policy was bent to cause increased medical risks, critical medical mistakes and grievous medical harms (including perinatal death), unnecessarily, for some of Norway's women and their fetuses/babies.

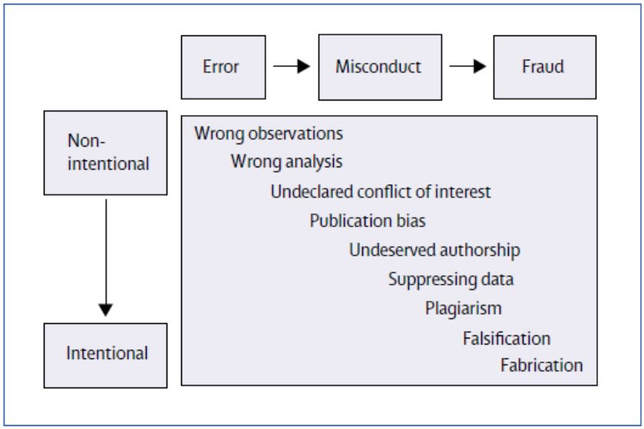

Ethics in Scientific Research

"Ethics in Scientific Research: An Examination of Ethical Principles and Emerging Topics"

"Key Findings

This research found ten ethical principles common across scientific disciplines

"Ethics in Scientific Research: An Examination of Ethical Principles and Emerging Topics"

"Key Findings

This research found ten ethical principles common across scientific disciplines

- They are duty to society; beneficence; conflict of interest; informed consent; integrity; nondiscrimination; nonexploitation; privacy and confidentiality; professional competence; and professional discipline. [See Table S.1 below]

- Each ethical principle applies to the scientific inquiry, the conduct and behaviors of researchers, or the ethical treatment of research participants.

- Only one ethical principle — duty to society — applies to the scientific inquiry by asking whether the research benefits society.

- Variations in ethical principles across disciplines are usually due to whether the discipline includes human or animal subjects.

- Variations in ethical principles across countries are usually due to local laws, oversight, and enforcement; cultural norms; and whether research is conducted in the researchers' host country or a foreign country.

- significant historic events that create a reckoning

- ethical lapses that lead researchers to create new safeguards

- scientific advancements that lead to new fields of research

- changes in cultural values and behavioral norms that evolve over time.

- Professional societies and peer-reviewed journals offer consistent ethical standards across national borders, though they lack the enforcement strength of nation-states.

- Emerging trends — including big data, open science, and citizen science — provide research opportunities while introducing new ethical risks.

- Professional societies respond to emerging changes with updates to codes of conduct, education and training for researchers, and governance structures for researchers, sponsors, and research subjects. (Source: "Ethics in Scientific Research: An Examination of Ethical Principles and Emerging Topics" by Cortney Weinbaum, Eric Landree, Marjory S. Blumenthal, Tepring Piquado, Carlos Ignacio Gutierrez. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0269-1. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2912.html. View/Download pdf here.)

Table S.1 (Source: Ibid., p. x)

Ethical Principles for Scientific Research

Ethical Principles for Scientific Research

Ethical Principle |

Definition |

Duty to society |

Researchers and research must contribute to the well-being of society. |

Beneficence |

Researchers should have the welfare of the research participant in mind as a goal and strive for the benefits of the research to outweigh the risks. |

Conflict of interest |

Researchers should minimize financial and other influences on their research and on research participants that could bias research results. Conflict of interest is more frequently directed at the researcher, but it may also involve the research participants if they are provided with a financial or nonfinancial incentive to participate. |

Informed consent |

All research participants must voluntarily agree to participate in research, without pressure from financial gain or other coercion, and their agreement must include an understanding of the research and its risks. When participants are unable to consent or when vulnerable groups are involved in research, specific actions must be taken by researchers and their institutions to protect the participants. |

Integrity |

Researchers should demonstrate honesty and truthfulness. They should not fabricate data, falsify results, or omit relevant data. They should report findings fully, minimize or eliminate bias in their methods, and disclose underlying assumptions |

Nondiscrimination |

Researchers should minimize attempts to reduce the benefits of research on specific groups and to deny benefits from other groups. |

Nonexploitation |

Researchers should not exploit or take unfair advantage of research participants. |

Privacy and confidentiality |

Privacy: Research participants have the right to control access to their personal information and to their bodies in the collection of biological specimens. Participants may control how others see, touch, or obtain their information. Confidentiality: Researchers will protect the private information provided by participants from release. Confidentiality is an extension of the concept of privacy; it refers to the participant’s understanding of, and agreement to, the ways identifiable information will be stored and shared. |

Professional competence |

Researchers should engage only in work that they are qualified to perform, while also participating in training and betterment programs with the intent of improving their skill sets. This concept includes how researchers choose research methods, statistical methods, and sample sizes that are appropriate and would not cause misleading results. |

Professional discipline |

Researchers should engage in ethical research and help other researchers engage in ethical research by promulgating ethical behaviors through practice, publishing and communicating, mentoring and teaching, and other activities. |

NOTE: Research participant refers to someone with an active role participating in research, whereas research subject could include someone whose data are used but who does not consent to participate.

Ethics in Scientific Research (continued)

Unethical laws & unregulated ethics...not enforceable & often not even monitored

Unethical laws & unregulated ethics...not enforceable & often not even monitored

- "As we examined laws, regulations, and standards around the world, we sought an understanding of the relationship between enforceable laws and unenforceable norms. We undertook this project with an understanding that laws can be unethical and ethics can be unregulated, and we hoped to understand how the administration of both laws and ethics may better align. We found that professional societies and journals aim to fill the gap between laws and ethics by documenting ethics that they expect of their members or authors, respectively; requiring members and authors to self-certify that they complied with such rules; and providing a reporting or grievance mechanism for cases in which members or authors self-report or are reported on. When these societies or journals have international membership or readership, they additionally seek to smooth out ethical differences from region to region by creating a discipline-wide standard. These mechanisms are imperfect, however, as they are not enforceable and often not even monitored." (Source: Ibid., p. xi-xii)

Evidence-based medicine (EBM)

"Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients' predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care." (Source: "Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't" David L Sackett, William M C Rosenberg, J A Muir Gray, R Brian Haynes, W Scott Richardson. BMJ 1996;312:71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. Published 13 January 1996)

"Evidence based medicine is not “cookbook” medicine. Because it requires a bottom up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients' choice, it cannot result in slavish, cookbook approaches to individual patient care. External clinical evidence can inform, but can never replace, individual clinical expertise, and it is this expertise that decides whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision. Similarly, any external guideline must be integrated with individual clinical expertise in deciding whether and how it matches the patient's clinical state, predicament, and preferences, and thus whether it should be applied. Clinicians who fear top down cookbooks will find the advocates of evidence based medicine joining them at the barricades." (Source: ibid.)

"There is an illusion that the ability to synthesise evidence provides all of the knowledge needed to practice medicine: that one has only to read the literature, or to adopt the guideline, to gain a mastery of the field. Governments, policy makers and payers have been seduced into believing that the rationalist EBM paradigm holds the solution to, for example, the task of providing high-quality medical care to an ageing population with complex needs. There is a push to codify and regulate the practice of medicine, to apply guidelines, and to pay for performance to standardise care, in the hope that this approach to evidence translation will reduce cost and improve outcomes that are of importance to institutions; Sackett warned of the risk of evidence-based medicine being hijacked to this purpose in 1996." (Source: "The 11th hour-time for EBM to return to first principles?" Denise Campbell-Scherer. BMJEvidence-Based Medicine 2012;17:103-104. DOI: 10.1136/ebmed-2012-100578. Pubmed ID22736667.)

"Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients or the delivery of health services. The terms ‘evidence-based health care’ and ‘evidence-based practice’ are often used interchangeably with ‘evidence-based medicine’" (Source: "SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP)" Report from Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services No 4–2010, Chapter 1, p. 16-25. ISBN print 978-82-8121-313-5, ISBN digital 978-82-8121-334-0, ISSN 1890-1298)

Evidence-informed health policymaking (EIHP) "evidence-informed health policymaking is an approach to policy decisions that aims to ensure that decision making is well-informed by the best available research evidence. It is characterised by the systematic and transparent access to, and appraisal of, evidence as an input into the policymaking process" (Source: ibid., p. 16-25)

Fetal Age Fetal age is the actual age of the developing and growing fetus/baby from the day of conception. Gestational age is the age of the pregnancy from the first day of the last normal menstrual period (LMP).

Fetal Biometry (also known as fetometery) "Fetal biometric parameters are antenatal ultrasound measurements that are used to indirectly assess the growth and well being of the fetus." (Source: Radiopedia: fetal metrics)

"Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients' predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care." (Source: "Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't" David L Sackett, William M C Rosenberg, J A Muir Gray, R Brian Haynes, W Scott Richardson. BMJ 1996;312:71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. Published 13 January 1996)

"Evidence based medicine is not “cookbook” medicine. Because it requires a bottom up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients' choice, it cannot result in slavish, cookbook approaches to individual patient care. External clinical evidence can inform, but can never replace, individual clinical expertise, and it is this expertise that decides whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision. Similarly, any external guideline must be integrated with individual clinical expertise in deciding whether and how it matches the patient's clinical state, predicament, and preferences, and thus whether it should be applied. Clinicians who fear top down cookbooks will find the advocates of evidence based medicine joining them at the barricades." (Source: ibid.)

"There is an illusion that the ability to synthesise evidence provides all of the knowledge needed to practice medicine: that one has only to read the literature, or to adopt the guideline, to gain a mastery of the field. Governments, policy makers and payers have been seduced into believing that the rationalist EBM paradigm holds the solution to, for example, the task of providing high-quality medical care to an ageing population with complex needs. There is a push to codify and regulate the practice of medicine, to apply guidelines, and to pay for performance to standardise care, in the hope that this approach to evidence translation will reduce cost and improve outcomes that are of importance to institutions; Sackett warned of the risk of evidence-based medicine being hijacked to this purpose in 1996." (Source: "The 11th hour-time for EBM to return to first principles?" Denise Campbell-Scherer. BMJEvidence-Based Medicine 2012;17:103-104. DOI: 10.1136/ebmed-2012-100578. Pubmed ID22736667.)

"Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients or the delivery of health services. The terms ‘evidence-based health care’ and ‘evidence-based practice’ are often used interchangeably with ‘evidence-based medicine’" (Source: "SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP)" Report from Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services No 4–2010, Chapter 1, p. 16-25. ISBN print 978-82-8121-313-5, ISBN digital 978-82-8121-334-0, ISSN 1890-1298)

Evidence-informed health policymaking (EIHP) "evidence-informed health policymaking is an approach to policy decisions that aims to ensure that decision making is well-informed by the best available research evidence. It is characterised by the systematic and transparent access to, and appraisal of, evidence as an input into the policymaking process" (Source: ibid., p. 16-25)

Fetal Age Fetal age is the actual age of the developing and growing fetus/baby from the day of conception. Gestational age is the age of the pregnancy from the first day of the last normal menstrual period (LMP).

Fetal Biometry (also known as fetometery) "Fetal biometric parameters are antenatal ultrasound measurements that are used to indirectly assess the growth and well being of the fetus." (Source: Radiopedia: fetal metrics)

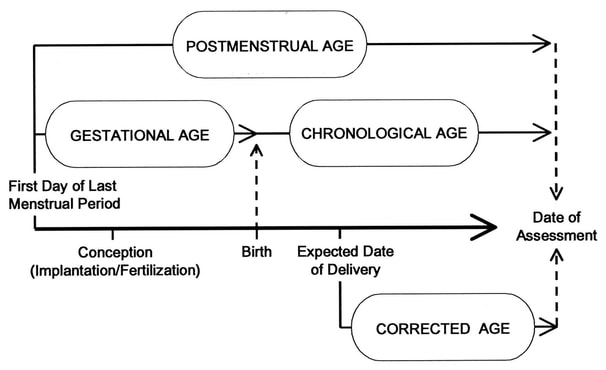

Gestational Age (GA) & Age Terminology

"Age Terminology During the Perinatal Period"

"Gestational age is often determined by the “best obstetric estimate,” which is based on a combination of the first day of last menstrual period, physical examination of the mother, prenatal ultrasonography, and history of assisted reproduction. The best obstetric estimate is necessary because of gaps in obstetric information and the inherent variability (as great as 2 weeks) in methods of gestational age estimation. 8,10,14–19 Postnatal physical examination of the infant is sometimes used as a method to determine gestational age if the best obstetric estimate seems inaccurate. Therefore, methods of determining gestational age should be clearly stated so that the variability inherent in these estimations can be considered when outcomes are interpreted. 8,10,14–19

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Standardized terminology should be used when defining ages and comparing outcomes of fetuses and newborns. The recommended terms (Table 1) are:

3. “Conceptional age,” “postconceptional age,” “conceptual age,” and “postconceptual age” should not be used in clinical pediatrics.

4. Publications reporting fetal and neonatal outcomes should clearly describe methods used to

determine gestational age."

"Age Terminology During the Perinatal Period"

"Gestational age is often determined by the “best obstetric estimate,” which is based on a combination of the first day of last menstrual period, physical examination of the mother, prenatal ultrasonography, and history of assisted reproduction. The best obstetric estimate is necessary because of gaps in obstetric information and the inherent variability (as great as 2 weeks) in methods of gestational age estimation. 8,10,14–19 Postnatal physical examination of the infant is sometimes used as a method to determine gestational age if the best obstetric estimate seems inaccurate. Therefore, methods of determining gestational age should be clearly stated so that the variability inherent in these estimations can be considered when outcomes are interpreted. 8,10,14–19

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Standardized terminology should be used when defining ages and comparing outcomes of fetuses and newborns. The recommended terms (Table 1) are:

- Gestational age (completed weeks): time elapsed between the first day of the last menstrual period and the day of delivery. If pregnancy was achieved using assisted reproductive technology, gestational age is calculated by adding 2 weeks to the conceptional age.

- Chronological age (days, weeks, months, or years): time elapsed from birth.

- Postmenstrual age (weeks): gestational age plus chronological age.

- Corrected age (weeks or months): chronological age reduced by the number of weeks born before 40 weeks of gestation; the term should be used only for children up to 3 years of age who were born preterm.

3. “Conceptional age,” “postconceptional age,” “conceptual age,” and “postconceptual age” should not be used in clinical pediatrics.

4. Publications reporting fetal and neonatal outcomes should clearly describe methods used to

determine gestational age."

Figure 1. Age terminology during the perinatal period.

(Source: "Age Terminology During the Perinatal Period" Pediatrics November 2004, VOLUME 114 / ISSUE 5

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS, POLICY STATEMENT, Organizational Principles to Guide and Define the Child Health Care System and/or Improve the Health of All Children, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. View/Download PDF here) [A Statement Of Reaffirmation For This Policy Was Published At 123(1):188 127(5):e1367 123(5):1421 134(3):e920; Policy Statement: Age Terminology During the Perinatal Period. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1362–1364. Reaffirmed July 2014]

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS, POLICY STATEMENT, Organizational Principles to Guide and Define the Child Health Care System and/or Improve the Health of All Children, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. View/Download PDF here) [A Statement Of Reaffirmation For This Policy Was Published At 123(1):188 127(5):e1367 123(5):1421 134(3):e920; Policy Statement: Age Terminology During the Perinatal Period. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1362–1364. Reaffirmed July 2014]

Gestational Age (GA) Notation & Math(s)

Gestational weeks are expressed as completed weeks. Gestational days are expressed as completed days.

Goodhart’s law

"Watch out for cheats in citation game"

Harm Principle (skadefølgeprinsippet)

Research Ethics Act

Health Systems & Policy Monitor (HSPM)

"The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies supports and promotes evidence-based health policy-making through comprehensive and rigorous analysis of the dynamics of health care systems in Europe."

Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

Gestational weeks are expressed as completed weeks. Gestational days are expressed as completed days.

- For example, day 3 of completed week 17 is expressed as: 17+3 or 17w+3 or 17w+3d or 17/3 or 17+3/7

- The first day of completed week 17 is expressed as: 17+0

- The last day of completed week 17 is expressed as 17+6; [Note: 17+7 is never valid; XXw+7 is never valid; XX+7/7 is never valid]

- The last day of completed week 17 is 17w+6

- The day after 17w+6 is 18w+0, which is the first completed day of completed week 18.

- GA in completed days: 17w+3 = (17 weeks x 7 days/week) + 3 days = (119 days) + 3 days = 122 days

Goodhart’s law

"Watch out for cheats in citation game"

- "All metrics of scientific evaluation are bound to be abused. Goodhart’s law (named after the British economist who may have been the first to announce it) states that when a feature of the economy is picked as an indicator of the economy, then it inexorably ceases to function as that indicator because people start to game it.

What we see today, however, is not just the gaming of science metrics indicators, but the emergence of a new kind of metrics-enabled fraud, which we can call post-production misconduct. It seems to be as widespread as other forms, with at least 300 papers already retracted because the peer review had been tampered with.

(...)

Given the increasing awareness of post-production misconduct— and how it undermines the assessment of publicly funded research — funders, policymakers and the science community should ask publishers to make available more of the information needed to investigate it.

The community must realize that, unlike previous fraudsters, from the unknown hoaxer who planted a mixture of bones in a British gravel pit at Piltdown to that of Paul Kammerer, who is blamed for inkingfeatures onto the feet of midwife toads to support Lamarckianism evolution, academic misconduct is no longer just about seeking attention. Many academic fraudsters aren’t aiming for a string of high-profile publications. That’s too risky. They want to produce — by plagiarism and rigging the peer-review system — publications that are near invisible, but can give them the kind of curriculum vitae that matches the performance metrics used by their academic institutions. They aim high, but not too high.

And so do their institutions — typically not the world’s leading universities, but those that are trying to break into the top rank. These are the institutions that use academic metrics most enthusiastically, and so end up encouraging post-production misconduct. The audit culture of universities — their love affair with metrics, impact factors, citation statistics and rankings — does not just incentivize this new form of bad behaviour. It enables it." (Source: "Watch out for cheats in citation game" "The focus on impact of published research has created new opportunities for misconduct and fraudsters, says Mario Biagioli." Nature 535, 201 (14 July 2016) doi:10.1038/535201a)

- "Intentional performance of an unreasonable act in disregard of a known risk, making it highly probable that harm will be caused. Willful negligence usually involves a conscious indifference to the consequences. There is no clear distinction between willful negligence and gross negligence." (Source: Legal Glossary: willful negligence) Also: "the type of negligence that is deliberate with the intentional disregard for other people's welfare." (Source: The Law Dictionary: Black's Law Dictionary: willful negligence)

Harm Principle (skadefølgeprinsippet)

Research Ethics Act

- "3.2. The Harm Principle as Guidance for Criminalisation

In light of this pragmatic tradition, a strongly principled statement on criminalisation was somewhat surprisingly given in NOU 2002: 4. Here, the harm principle (skadefølgeprinsippet) was adopted and applied as a principal starting point for the criminal code. The code of 2005 is based on the idea that punishment should solely be used as a reaction towards actions that lead to, or could lead to, harm being inflicted on someone. 24 The idea is that a specific behaviour should not be criminalised only because the majority dislikes it. The use of punishment must be rational and humane. 25 Punishment should only be used in cases where compelling reasons justify it, and actions that lead to the harm of people or assets will typically constitute such compelling reasons. The harm principle was the fundamental starting point for the work of the Legislative Commission of the Criminal Code. 26" (Source: "An Outline of the New Norwegian Criminal Code" JØRN JACOBSEN & VILDE HALLGREN SANDVIK. Bergen Journal of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice • Volume 3, Issue 2, 2015, pp. 162-183)

Citation References [links added]

24 This was set out in NOU 2002: 4, see in particular pp. 79-81.

25 Ot.prp. nr. 90 (2003-2004) p. 89

26 NOU 2002: 4, p. 79.

Health Systems & Policy Monitor (HSPM)

"The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies supports and promotes evidence-based health policy-making through comprehensive and rigorous analysis of the dynamics of health care systems in Europe."

- HSPM: http://www.hspm.org/

- Norway's Health Care System: http://www.hspm.org/countries/norway08012014/countrypage.aspx

(Source: http://www.euro.who.int/en/about-us/partners/observatory/about-us)

Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health (Helsedirectoratet) defines Health Technology Assessment (HTA) as follows.

"HTA Health Technology Assessment. Tools that will help to make knowledge-based decisions when introducing new methods in the health service. Should elucidate the effects and safety-related, health-economic, ethical, legal and social consequences of the method"

"HTA Health Technology Assessment. Vektøy som skal bidra til å ta kunnskapsbaserte beslutninger ved innføring av nye metoder i helsetjenesten. Bør belyse effekt og sikkerhetsmessige, helseøkonomiske, etiske, juridiske og sosiale konsekvenser knyttet til metoden" (Source: "Guide for the development of knowledge-based guidelines" ("Veileder for utvikling av kunnskapsbaserte retningslinjer") Redaktør: Caroline Hodt-Billington. Utgitt: 10/2012. Publikasjonsnummer: IS-1870. ISBN-nr. 978-82-8081-225-4. Utgitt av: Helsedirektoratet, 2012. p. 7)

View/Download Norwegian Directorate of Health's 2-page "Checklist for the development of knowledge-based guidelines" (Sjekkliste for utvikling av kunnskapsbaserte retningslinjer) View/Download Norwegian Directorate of Health's 58-page "Guide for the development of knowledge-based guidelines" (Veileder for utvikling av kunnskapsbaserte retningslinjer) (Source: Helsedirectoratet website: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/utvikling-av-kunnskapsbaserte-retningslinjer)

- "What is Health Technology Assessment (HTA)?

HTA is the systematic evaluation of the properties and effects of a health technology, addressing the direct and intended effects of this technology, as well as its indirect and unintended consequences, and aimed mainly at informing decision making regarding health technologies. HTA is conducted by interdisciplinary groups that use explicit analytical frameworks drawing on a variety of methods." (Source: "Welcome to INAHTA" INAHTA Website: http://www.inahta.org/)